Shingles threatens man’s vision, life

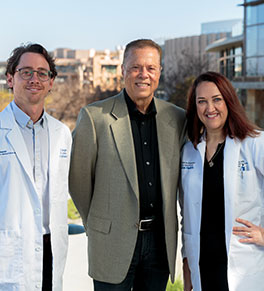

Bill Rowcliffe says he owes not just his vision, but also his life to quick action by his doctors at the UCI Health Gavin Herbert Eye Institute.

Last summer, eye institute ophthalmologists diagnosed him with a rare case of shingles that had inflamed his optic nerve, requiring a trip to the emergency room. He ultimately spent six days in the hospital, treated by a team of eye doctors and specialists in neurology and infectious disease.

“The ophthalmology team did a great job treating him while he was at the hospital,” says Rowcliffe's wife, Clayre Petray. “I think they’re the reason he’s alive today.”

It all started in spring 2024, when he developed a case of shingles that affected his face. Caused by the same zoster virus as chickenpox, shingles is a painful red rash that occurs most often in older adults. When the rash appears on the face, it can also inflame the cornea and other areas of the eye, potentially leading to irreversible vision loss.

Rowcliffe sought care at the eye institute, where he was prescribed antiviral medication and eye drops. They can help prevent vision loss in shingles patients — as long as the inflammation is treated before causing permanent damage to the cornea.

“Shingles on the face is considered an eye emergency because it can lead to serious complications if not treated urgently,” says Rowcliffe's neuro-ophthalmologist, Dr. Samuel J. Spiegel.

Blurred vision

Rowcliffe thought he was on the mend until he began experiencing blurred vision a few weeks later. He returned to the eye institute for what Spiegel described as "an extremely uncommon neurological side effect caused by the disease."

Cornea specialist Dr. Marjan Farid examined the optic nerve in Rowcliffe's left eye and immediately called Spiegel. They huddled outside the exam room to confirm their diagnosis: post-shingles inflammation was causing fluid to build up on his optic nerve, which could lead to vision loss and even blindness.

They immediately sent him to the emergency room at UCI Health — Orange, formerly known as UCI Medical Center.

Rowcliffe was quickly admitted to the hospital, where Farid and Spiegel continued to manage his care in coordination with neurologists, emergency medicine specialists and infectious disease experts.

No established protocol

Cases of post-shingles inflammation of the optic nerve are so rare that there is no widely accepted best practice for treatment.

Farid and Spiegel consulted across departments at the academic health system and even with colleagues at other institutions before deciding to proceed with high-dose intravenous steroids in tandem with anti-viral treatment. The course of treatment worked to reverse the inflammation.

“My overall experience — other than it being the worst thing that’s ever happened to me — is that UCI Health has a great team,” says Rowcliffe.

Over the last year, his vision continued to improve with ongoing care under the watchful eyes of Spiegel and Farid. Eventually, he was able to resume his regular routine: reading, driving and playing pickleball.

“I can see to make contact with the ball again on the pickleball court,” says Rowcliffe, whose vision is back to 20/30.

“I’m very grateful to my all doctors, especially my ophthalmologists.”

Learn more about eye care services at the UCI Health Gavin Herbert Eye Institute ›

Related stories

- Removing blinding cataracts brightens autistic teen’s outlook ›

- Envisioning the future of eye care ›

- Giving the gift of sight ›

- Eyes are a window into the brain ›